Human Resilience in a Financial World

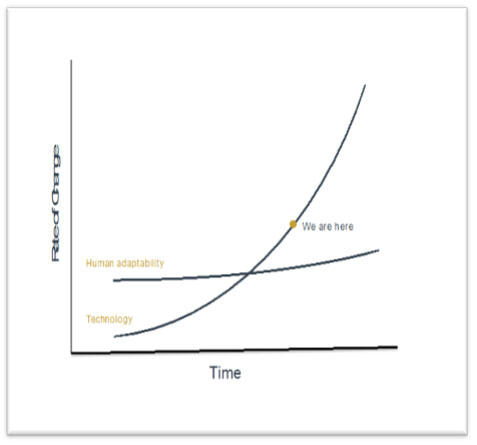

Historically, knowing or needing to know the capability and capacity of one’s workforce was irrelevant when the individuals’ ability to cope (and keep up) was seen as being greater than the working equipment/environment around them. However, the advent and then endemic use of computers has revolutionised the world of work; particularly, in the financial sector where, in this context, it is the poor humans’ capability that is lagging way behind (See Figure 1). Perhaps this is revealed most starkly in the financial sector where a significant number and scale of transactions happen globally daily – for example, in 2019, there were an average of 708.5 billionnon-cash transactions per day. The prospect of financial institutions being forced in to a position where they can not operate resultant from absent staff and/or staff who are present but performing sub-optimally is catastrophic at both a local (national) and international level. Whilst the global Covid-19 pandemic has certainly brought such operational resilience (or lack of) in to sharp focus, once a century events should not differentially influence meritorious and rationale decision making to meet financial requirements too greatly.

Figure 1: Graph to demonstrate Moore’s Law – how technology is evolving at a far greater rate than our ability as humans to adapt (Moore G. E. 1965)

In its capacity of supervising financial market infrastructures (FMIs), the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), and the Bank of England (“the Bank”) collectively known as “the supervisory authorities” have put in place a stronger regulatory framework to promote the operational resilience of firms and FMIs. The proposals were designed to improve their operational resilience and protect the wider financial sector and UK economy from the impact of operational disruptions. The consultations proposed requirements and expectations for firms and FMIs to:

- Identify their important business services by considering how disruption to the business services that they provide can have impacts beyond their own commercial interests

- Set a tolerance for each important business service, and

- Ensure that they can continue to deliver their important business services and are able to remain within their impact tolerances during severe (or in the case of FMIs, extreme) but plausible scenarios

…. with the Supervisory Statement 1/21 (Operational Resilience: Impact tolerances for important business services) being effective from Thursday 31 March 2022.

One of the pivotal components in all of this, are the employees themselves – particularly, their health and wellbeing – and that they are fit and able both to attend work (whether home or office) and perform adequately (preferably optimally) – it is often said that “there is no performance without wellbeing”. One of the challenges with human beings is that they are a complex – and within this context – an amalgam of physiological and psychological processes and needs which historically have been at best very hard to or, at worse, impossible to measure and then nurture; especially, the psychological ones. Occupational Health and HR professionals have for years dreamed of truly knowing individual by individual, group by group and organisationally the true level of stress that people are under, what causes it (its components) and perhaps, most importantly, what can be done individually and organisationally to mitigate this. Historically, Pulse surveys (questionnaires) have been used; however, these have simply generated the data that the respondent wants (or thinks that) the recipient (organisation) wishes to receive (especially in highly competitive environments like the financial sector) – with all of the inherent inaccuracies, biases and opportunities for a lack of honesty, exaggeration or denial – rarely the true position.

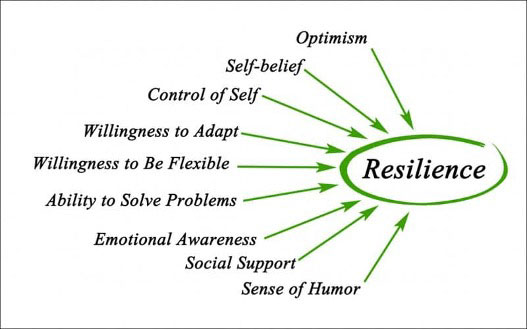

For the purposes of clarity within this article, “Resilience”, in a psychological sense, is defined as “compromising a set of flexible cognitive, behavioural and emotional responses to acute of chronic adversities which can be unusual or commonplace. These responses can be learned and are within the grasp of everyone; resilience is not a rare quality given to a chosen few. While many factors affect the development of resilience the most important one is the attitude you adopt to deal with adversity. Therefore, attitude (meaning) is the heart of the resilience” (Neenan and Dryden, 2009).

So, in essence, Resilience is a number of different but related aspects (See Figure 2):

- An ability to cope with stress

- An ability to manage ones emotions (not suppress them)

- A mental toughness or “hardiness” – remaining resilient despite difficult circumstances

- An ability to bounce back from or overcome adversity

- Related to the meaning (attitude) people attach to adverse events (perspective is important

Figure 2 – components of psychological Resilience

The hours of work and levels of stress that those in the financial sector are under is widely known but what often remains unseen is the burgeoning levels of fatigue and compromised physical/cognitive capabilities as the norm; and, where draconian sickness absence policies/processes/procedures exist, then rising levels of presenteeism and plummeting individual wellbeing and organisational wellness results. However, such technology is now available to measure many biometric, psychological and contextual variables and with these calculate truly dynamic measures of individual, group and organisational capacity and resilience.

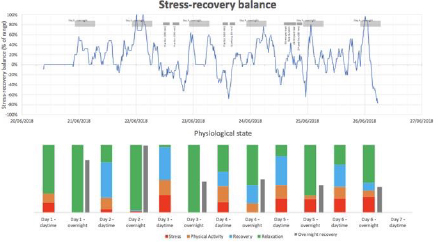

For many years cardiologists have measured an aspect of the beat of the heart – called Heart Rate Variability (HRV) – which, in simple terms, is a measure of the variation in time between each heartbeat. It responds not only to poor sleep, or a negative interaction with a manager or colleague but also to positive stimuli such as promotion/pay-rise. Our bodies can handle all kinds of stimuli daily and day-after-day – yet, “life goes on”; however, if one or more stimuli persist such as stress, poor sleep, duration of work, unhealthy diet, dysfunctional relationships (work, personal and domestic), isolation or solitude (social connectivity), compromised finances, and lack of exercise, then this balance may be disrupted, and the individuals’ fight-or-flight response can move into “overdrive”.

HRV can be measured with an unobtrusive wrist worn “wearable” and then forms the basis of the measurement of stress, wellbeing, recovery, etc. wherein the use of sophisticated algorithms generates insightful data individually, for groups and the organisation holistically (See Figure 3). By blending other data such as work activity it is also possible to build models that offer an insight into the ‘mental cost’ of a task; and, therefore, understand the mental demands and individual and organisational capacity and resilience. Monitoring over time provides the opportunity to build biorhythm models and predict how individuals, teams and organisations will respond to different situations and needs.

Figure 3: Time Series HRV analysis mapping recovery (above 0%) and stress (below 0%) balance. Image courtesy of IHP-Analytics Ltd

The techniques described herein have been developed and honed in the brutally exacting world of Formula 1; and, whilst sport presents a comparatively easy environment in which to harvest data, advances in General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), data security and data architecture mean that this technology and expertise can be applied to organisational resilience strategies reliably and robustly. Mental health, total worker wellbeing and stress are already key items on the agenda for businesses, often down to the increase in demand on our attention by different forms of technology and data at increasing pace (Figure 1). The ability to monitor how stress is impacting performance, resilience and wellbeing, together with the potential to perform proactive intervention strategies will become a necessity for modern organisations looking for agility and individual/organisational resilience in current times. It is worthy of note that whilst stress is increasingly documented as a bad thing, stress response through the ANS is a perfectly normal human response mechanism. Stress, seen as an occurrence or as a preparation to perform (for instance), should be seen as good as well as normal. It is only when stress falls outside of an individual’s ‘norms’ and/or becomes cumulative or chronic should it become a cause for concern.

Far from just providing individual insight, HRV data in combination with other data can be used to inform leadership about team dynamics, cultural strategy and engagement. It could even feedback on their own leadership attributes and performance. Put simply, by integrating biometric data such as HRV with other factors it is possible to turn previously intangible human workforce behaviours and responses into tangible metrics. Workforce data in this format have the ability to empower organisations with agile, tangible and potent HR and OH strategy. It provides robust quantitative data rather than the traditional subjective self-completed questionnaire type data so commonly deployed currently and provides a new level of objective assessment that has the potential to connect employee to employer and provide benefit to both parties in unison. Additionally, comparison of subjective responses with biometric indicators provides excellent opportunity to challenge innate bias’ and perceptions that naturally detract from cohesion, engagement and team dynamics, and can form the basis for optimised and truly individualised resilience development programmes.

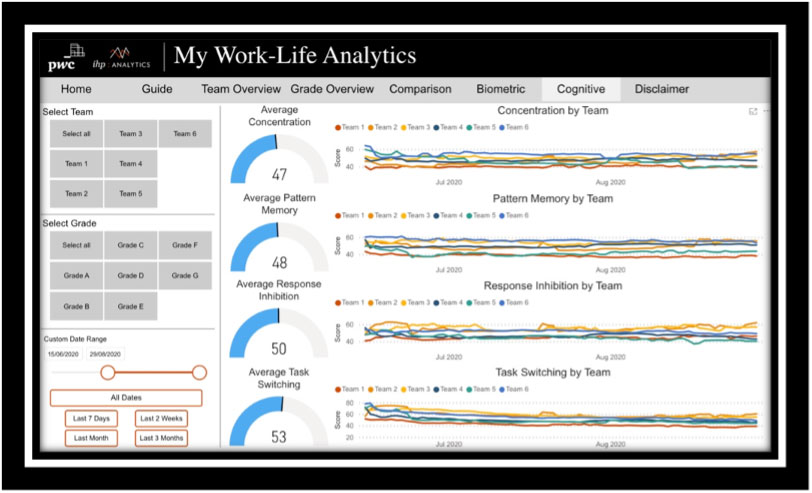

Figure 4: Illustrative dashboard of real time user feedback on the basics of sleep, rest, recovery, stress and activity. Graphics reproduced by kind permission of IHP-Analytics Ltd (My Work Life AnalyticsTM) www.ihp-analytics.com –

Once stress, body battery/recovery, and resilience can be measured quantitatively along with the work-related factors influencing individuals and/or groups, then organisations can begin to look at ways of improving wellbeing, performance and ultimately resilience. In almost every instance, quantum gains can be made in focusing on the core physiological basics that interplay with stress and that are readily affected by technological advances: sleep, activity, rest and recovery. It is likely that an improvement in one of these basic human functions will change the individual’s ability to manage the stress and optimise resilience more effectively. Conversely, cumulative stress can impact upon our ability to perform the others well too; hence, it is better to provide a holistic viewpoint with an idea of what change will provide the greatest impact (Figure 4 + 5) to facilitate simple indications for change.

Figure 4

Providing accurate, work-specific data to individuals, teams and organisations in itself can be a major instigator for change. A combination of bringing a metric to a previously ‘unknown known’ together with direct context that relates to the user is a powerful motivator in comparison to a theoretical model or generic training. This breeds ‘self-awareness’, a conscious rational understanding that quashes our previous beliefs directly. An example, would be our internal perception of stress, i.e. “I feel stressed/under pressure”, a normal emotional response. Real time data quantifies that response and provides (in most instances) a realisation that perception is greater than actual stress, both initiating a natural internal ‘thermostatic’ response that modifies the reaction and a basis for instigating a coping strategy such as deep breathing exercises.

Figure 5

Fundamentally HRV data, with stress and fatigue as the leading OH indicators can now form the basis of accurate, optimised performance and wellbeing strategies, enhancing the agility and resilience of an organisation, potentially allowing it flex (and particularly its workforce) within an increasingly turbulent workplace. For the first time, it is feasible for HR/OH professionals to assist a business to see itself as a living organism and hence make data-driven decisions to optimise its performance and wellbeing.

Whilst there are challenges to collecting personal data from a GDPR and data security perspective, in addition to the occasional misguided user and/or dissenter incorrectly using the capability or trying to create a negative perspective/reputation that could be attached to the perspective of overtly ‘monitoring’ employees for the good of the organisation – this certainly does not have to be the case. When programmes are designed and driven by OH and human science professionals (wherein the individual is empowered to drive their own change journey) – there is a significant value and benefit to the employee in using data to understand how to optimise their work-life balance, and from the organisational perspective to assist the organisation strategically to hone their human resource and wellbeing functions accurately. With careful application of the technology, human analytics has the potential to greatly enhance the employee experience and thus positively impact productivity, engagement and mental health (amongst other things). As with other areas of technological growth, the more data that can be collected, the greater the ability for organisations to refine and optimise their commitment to wellbeing, with the potential to use predictive analytics to support their workforce proactively rather than dealing with expensive reactive intervention.

The advent of both the HRV-wearables and the sophisticated algorithms which take the psychometric, biometric, cognitive and contextual data which turn this disparate information in to meaningful metrics that drive personal behavioural change and, at an organisational level, utilise the pseudoanonymised information to make fundamental and strategic changes – the impact of which can be observed in almost real-time to enable subtle corrections. The following are some of the techniques used to affect Resilience at Work

- Optimising the quality of working life

- Awareness, attitudes and behaviours

- Implementation intentions (for work pressures)

- Strengths and person-job fit (flow)

- Sustainable employee engagement

- Positive communication

- Control and acceptance; enabling control

- Positive working relationships and support

- What-went-well

- Fining meaning and purpose at work

….. the impact and sustainability of these interventions can all be measured and optimised.

The opportunity is now!